Designing in a State of Climate Emergency¶

Too Long Didn’t Read

This week’s module was deeply philosophical, exploring what it means to be a designer in our current state of climate emergency. Led by Andres Colmanares and Gustavo from Temporality Lab, we discussed designing in a Polycrisis and the concept of “The Long Now” – viewing time as a 3D torus where past, present, and future coexist. We examined degrowth, green growth, and the need for economic models prioritizing sustainability. Through public interviews and discussions, we gained insights into people’s perceptions of climate change and the futures they envision. The module underscored the importance of systems thinking, interdisciplinary collaboration, and long-term sustainability in design.

I said, empty your mind. Be formless. shapeless. like water. Now you put water into a cup. it becomes the cup, you put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle you put in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Water can flow. or it can crash. be water, my friend. – Bruce Lee

In an era where the term “climate emergency” has become a frequent headline, comprehending the depth and breadth of this crisis is daunting. This week’s module was a much more philosophical one. Led by Andres Colmanares of IAM and a guest lecture from Gustavo from Temporality Lab, we dove into what it means now to be a designer in our current state of climate emergency and ask ourselves…

“What kind of future will the next billion seconds create?”

Discovering the Polycrisis¶

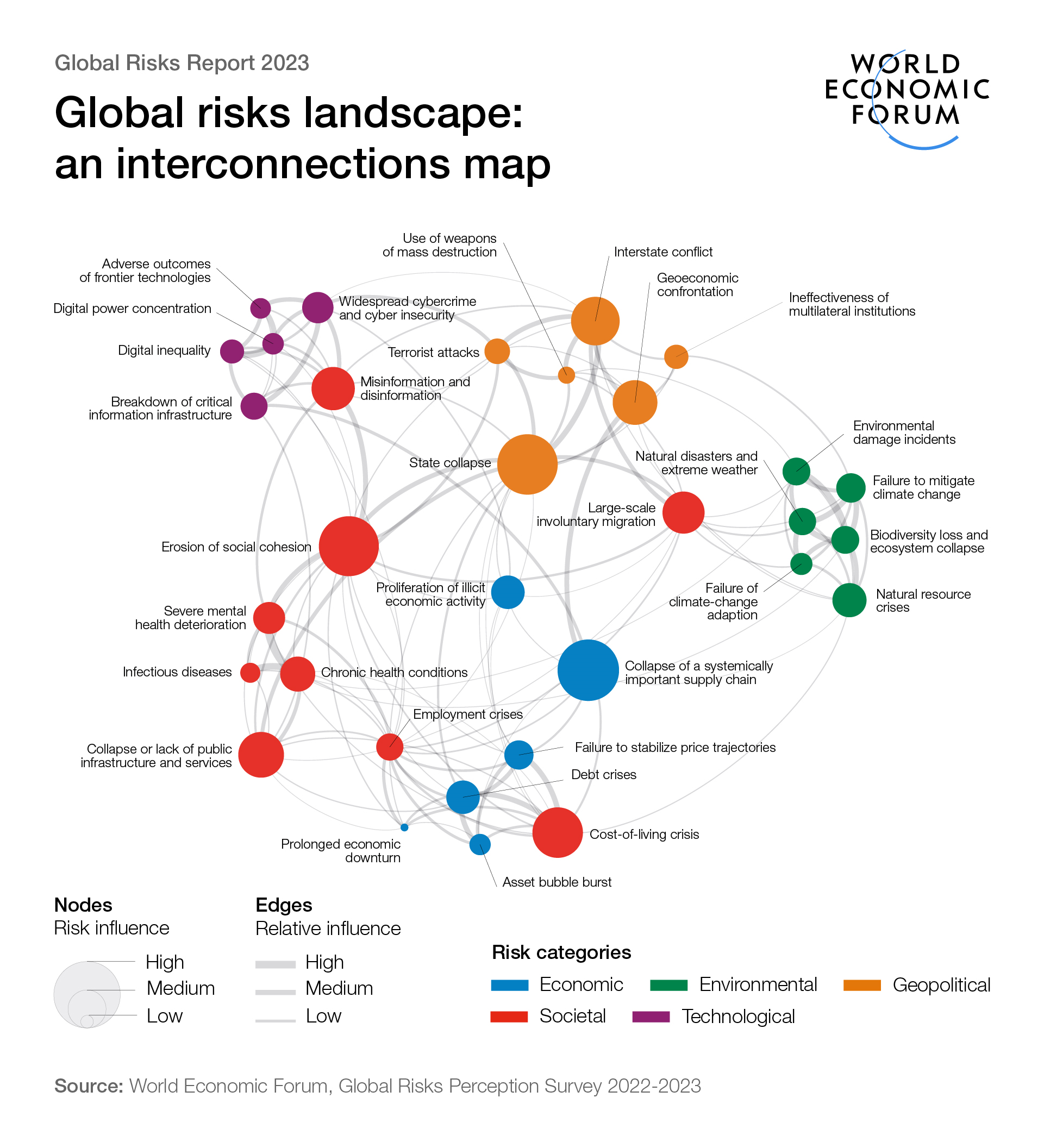

What does it mean to design in a state of Polycrisis? when Andres first introduced us to the concept I didn’t understand it either, so it’s important to understand exactly what the term means.

First popularised at the world economic forum in 2023 to try and describe the multitude of issues facing the world right now, the concept of ‘Polycrisis’ - suggests that the world is facing unprecedented pressure from various directions simultaneously, creating a situation that appears incoherent and overwhelming. Encompassing economic, political, geopolitical, and environmental issues, which do not have a single common denominator. The term helps understand how modernization, economic development, and capitalism have contributed to these interconnected crises, including climate change, pandemics, geopolitical tensions, and democratic dysfunction.

There are four key factors that contribute to the uniqueness of our current Polycrisis:

- Human Energy Consumption: The exponential increase in human energy consumption, primarily through fossil fuels, and its significant impact on the environment.

- Earth’s Energy Balance: The importance of understanding the balance between the energy Earth receives from the sun and the energy it emits back into space. This balance is crucial for Earth’s climate and is being altered by human activities.

- Anthropogenic Biomass: The concept that the total mass of human-created materials (like concrete, bricks, and other building materials) has now surpassed the total biomass of all living creatures on Earth. This shift has significant implications for the planet’s ecosystems.

- Connectivity of Human Populations: The interconnectedness of the global population, not just in terms of digital communication but also through supply chains and global commerce. This interconnectedness exacerbates the impacts of crises in one area on the entire global system. Illustrated by a video on the supply chain crisis.

It is these factors, occurring simultaneously, that represent a unique challenge in human and planetary history.

The idea of Polycrisis resonated with me deeply. It presents a wicked problem, not just as a singular environmental crisis but as a complex web of interconnected issues without a single root cause. A design problem that cannot be solved by individual groups working in silo to achieve a single solution and then moving on to the next, but by multiple groups of interconnected people working towards and sharing information to help facilitate the transition into a better future.

As designers, we have to take a step back and see the bigger picture. We must approach solutions considering the many ways in which different crises interact and impact one another, and the solutions we do end up creating must consider the vast scale and complexity of these interconnected problems.

Time and Perception¶

The “Long Now”, is a method of stretching the concept of now to the next 2,000 years and the past 2000 years, asking ourselves how are we being influenced by the past and what impact are we going to have on the future with the actions we take right now - A more long-term view

Gustavo’s lecture introduced an angle that I hadn’t really considered before when it comes to design - our perception of time and its cultural interpretations. He explored how various cultures perceive time and its influence on actions and decisions. The most striking concept was ‘positional temporality,’ a notion that encourages viewing time not as a linear progression but as a 3D torus, where past, present, and future coexist and influence each other, particularly as they all return to the present moment.

This concept encourages us all to (and this is something I wholeheartedly agree with) make design decisions that embrace a much longer timeline when considering the impact of the objects, services or policies that we create. Which hopefully allows us to make decisions (as best as we can with the information and weak signals we can identify) that ensure the artefacts we create do not have a negative effect on the environment and future generations to come when they reach their end of life.

This type of thinking is already being taken into consideration in the design of products through innovation in repairability, bio-based materials, modularity and subscription models, while policies like “Right to Repair” bills are being pushed through by the EU and California to name a couple.

I for one, am all for it.

The Economics of Degrowth¶

Throughout the week we held discussions on degrowth and the possibility of green growth. It was intriguing to see diverse perspectives on growth and its implications in our current economic systems. Donut economics emerged as a compelling alternative, suggesting a balance between human needs and ecological limits.

Personally, I believe we need to have a fundamental shift in how we perceive value, and that we shouldn’t base the success of a city or nation on how much Gross Domestic Product it produces, as this requires a system of constant growth which has played some part in the ecological mess we find ourselves in now. Perhaps we need to shift more towards measuring through other metrics, such as Gross National Happiness (GNH) or Thriving Places Index (TPI), by using metrics so as these we can (I believe anyway, and I could be very wrong) that we can still prosper and grow as a society while boosting economic prosperity and remain within planetary and social boundaries.

You can find more on different indexes of prosperity here.

These discussions fed my interest into transition design further, and got me thinking about how we could use design thinking methods to help create and improve policies that attempt to improve the welfare of everyone in a city, state or country. This is something I want to explore further in this degree.

Public led interviews¶

The module wasn’t just theoretical; it included hands-on activities that allowed us to apply our learnings. We took part in a group exercise and involved the public as well. Designing a rough ‘guerrilla’ style poster, we interviewed people along Barcelona Beach about their perceptions of climate change and got them involved by asking a simple open question: “What is the kind of future you would like to see?”. Prompting them to answer with one word at first, these discussions led to some really interesting insights and understandings of the kinds of futures that people wanted to see come about, and almost all of them included and world in which we had managed to get our heads around climate change and developed fairer and more just solutions to the issues it presents.

It’s opened up some interesting areas for further development and research in this field, through hardware, software and policy, and I think that design is the best field positioned to help facilitate these changes.

Designing for the next billion seconds¶

The module underscored the urgency and complexity of the climate emergency and highlighted the pivotal role designers can play in addressing it. We delved into the layers of environmental crises, the multifaceted nature of time, and the critical need for economic models that prioritize sustainability over mere growth.

This journey has been about more than just absorbing information; it’s been an experience that has shifted and often times reinforced some of my beliefs in the potential and responsibility of design. The idea of Polycrisis, in particular, stands out to me as a crucial framework for approaching and understanding systems and problems for future design work.

It’s no longer sufficient to tackle problems in isolation; we must adopt a holistic approach that acknowledges the interconnectedness of global challenges.

As Andres emphasized, our role is not merely as residents of planet Earth, but as integral parts of the entire ecosystem. As we navigate the complexities of designing in a climate emergency, It’s all about balancing the immediate needs with long-term sustainability, considering the cascading effects of our design choices on future generations.

In Gustavo’s exploration of time, what stuck with me the most is the idea of seeing time as a 3D torus, where past, present, and future are interwoven. This view on the flow of time has profound implications for the way we design not just products, but services and policies too. It encourages us to create with a consciousness that our present actions are future histories, thereby fostering a sense of responsibility and foresight in our designs. Where we can start to implement some version of the “Long Now” perspective.

Our present actions are future histories

As I conclude this reflective journey, I am left with a renewed sense of purpose and a clearer vision of the role I wish to play as a designer. The lessons learned here are not just theoretical musings but practical tools and perspectives that I will carry forward in my work.

The challenge now is not merely to adapt to the current climate emergency but to actively participate in shaping a sustainable and equitable future. As designers, we have the unique ability to envision and create that future. We are not just problem-solvers; we are storytellers, strategists, and agents of change. Our designs can influence behaviours, shape cultures, and ultimately, contribute to the well-being of our planet and its inhabitants.

In the words of Gustavo, “We are the authors of time.” Our designs are not just products or services; they are time capsules that carry our values, hopes, and visions into the future.

How can we apply these learnings to design right now?¶

Here I will leave you with some key learnings and values that I think can be implemented into design practice right now, and is something I am certainly going to do my best to achieve. It’s not always going to be possible to do with all the constraints that projects can have, but beginning a project with some of these in mind might just be enough to steer them in a better direction 😁

- Embrace Systems Thinking

- Understand the interconnectedness of various crises. As a designer, consider the broader impact of your designs on social, economic, and environmental systems. Aim to create products that not only solve individual problems but also contribute positively to these larger systems.

- Foster Adaptability and Resilience

- Design products that are adaptable to changing environments and user needs. This could mean creating modular or multi-functional products that can evolve over time, reducing the need for replacement and waste.

- Embracing Time and Cycles in Design

- If time can be viewed as cyclical, this suggests a need to shift from linear to cyclical design thinking. This means considering the lifecycle of products, from creation to disposal, and designing for sustainability, reparability, and longevity.

- Human-Centred vs. User-Centred Design

- Consider broader human values and social contexts. It’s about understanding the deeper human experiences and emotions associated with a product, beyond its utility.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration

- The design process can benefit greatly from insights and inputs from fields like environmental science, sociology, cultural studies, and even philosophy to create more holistic and contextually relevant products.

- Narratives and Storytelling

- Embedding narratives into your products can create a deeper connection with people, making them more than just objects but carriers of stories, values, and meanings. This can be achieved through the design process, materials used, or the way products are marketed.

- Reflection of Cultural and Ecological Sensitivity

- Integrate local cultural insights and ecological considerations. This means respecting and learning from traditional knowledge systems and designing products that are in harmony with local ecosystems and cultural practices.