Bio Zero

Too Long Didn’t Read

This week, we immersed ourselves in Biology Zero with Nuria Conde, learning the foundations of microbiology, gene editing, and the potential of CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Though I missed the classes, my classmates helped me catch up. We collected and cultivated bacteria, explored microbiology’s impact on climate change, and grew Spirulina and Kombucha in practical sessions. Our project involved designing a genetically modified organism (GMO) to solve a problem. I proposed a sunflower and mangrove hybrid that could clean polluted soils through phytoremediation and thrive in harsh conditions. This project highlighted the potential of using biology in design, showing that nature could be our next big design partner.

For the past week, we have been immersed in Biology Zero Taught by Nuria Conde. A series of lectures and practical experiments focusing on exploring and understanding the basic building blocks of life that make up the world we live in into the complexities of multi-celled lifeforms. and how those building blocks can be changed and edited through new technologies such as Crispr-Cas9 to make new and exciting changes that could benefit life on spaceship Earth.

Unfortunately for me, I was away this entire week and so unable to attend all my classes, but my classmates very kindly offered to catch me up on what I’d missed in person (thank you, Carlotta, for your notes 😅) as well as allow me to stream into one of the classes live via video call to see what was going on during a practical. What follows is my understanding and interpretation of what we learned (or what I was supposed to learn).

The days were split into two sections: the mornings, where we learnt about the foundations of microbiology, gene editing, how Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) are used today and what the potential is for the future of gene editing technology in a world affected by climate change. while the afternoons were for putting that theory into practice.

Intro 101¶

The session on the first day of the course was to collect and cultivate bacteria that would grow overnight for study the next day. The process began with preparing a food source for the bacteria to thrive. In this case, we used a lab yeast medium. Mixed with peptone (which acts as a protein source), Yeast (a source of carbs), sugar (encouraging osmosis) and agar to make it all gel together. These growth mediums were then combined with various bacteria samples collected from the surrounding environment and placed into the incubator overnight.

The long view¶

The following day, the group returned to find that the incubator had malfunctioned, and all the bacteria had failed to flourish just yet. No examining tiny organisms for the moment.

As the machines were being recalibrated, we were given a lecture on microbiology, how classification works when identifying lifeforms on Earth and how climate change is affecting life right down to the microbial level. Our teacher Nuria explained that in biology, one must take a much longer view of things (something I found very interesting when hearing about this from my classmates, as so much of our decision-making now in all walks of life is based on short-term gain or loss, and given my interest in Long-Termism planning methods) and that over the centuries that planet will fluctuate and it’s environments will change — naturally yes, but definitely exacerbated by humans and climate change — and that while we may go extinct, there are many other species that will adapt and thrive in these new climates. So, indeed, life finds a way…

I think it’s pretty important to remember that we are stewards of our planet after all, and the most sustainable thing we can do is to try and plant trees whose shade we will never sit under (in every sense of the metaphor).

The afternoon practical introduced the group to the microscopic world and the wonders of that tiny universe that lies just out of sight. The exercise was for everyone to try to understand the complexity hidden in just one drop of pond water on a glass slide and how these basic organisms form some of the organics we rely on every day. As a bonus, they are really quite beautiful to look at 😃

Gene Editing & Spirulina¶

The third-day dove head first into gene editing, the technologies that make it possible, and what can be done with it.

This was further developed in the practical (which I could attend via video call) of growing our own strain of Spirulina, an algae considered a superfood due to the high amount of protein, vitamins and nutrients it contains and understanding its many applications. During the session, the group prepared the ideal growing environment for the algae — no better way to learn than by doing! While they were at it, they also attempted to grow a small piece of Kombucha that Nuria had provided.

Designing a GMO - Cleaning contaminated marshlands using a sunflower and mangrove hybrid¶

Type: Biology Zero Professor: Nuria Conde

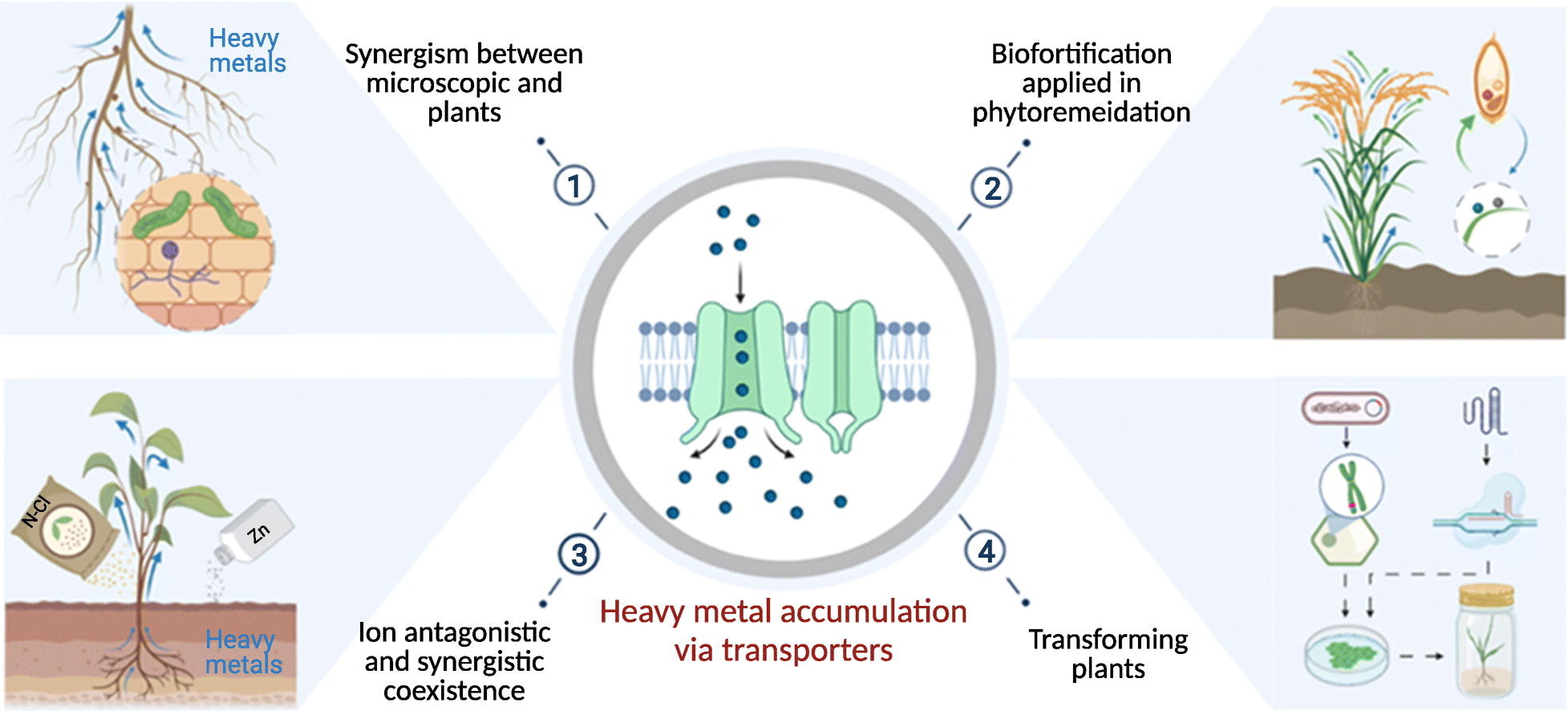

For this week’s project, we had to write a creative proposal for the creation of a new genetically modified organism that could solve a problem in the world. I decided to focus on using the unique properties of sunflowers(Helianthus annuus L.) that enable them to clean up pollutants such as heavy metals from the soil they grow in, a process known as phytoremediation and splicing in a series of genes taken from mangrove trees (Rhizophoraceae) that allows them to thrive in much harsher and saltier conditions that would be deadly to most other plant life found on land. Creating a new sunflower hybrid that could be planted in areas of land considered too polluted, degraded or marshy for other types of life. Cleaning up the surrounding soil by removing contaminants and leaving healthier, cleaner soils behind.

Sunflowers are one of the most widely used plants for phytoremediation, as they can accumulate various metals and organic compounds from the soil, such as cadmium, lead, arsenic, and uranium. Sunflowers also have high biomass production, fast growth rate, and high seed yield, making them economically valuable and easy to cultivate. However, sunflowers are sensitive to salt stress, which limits their application in saltwater-contaminated soils.

Mangrove trees are a group of tropical and subtropical plants that grow in intertidal zones along the coastlines. Mangrove trees have evolved remarkable adaptations to cope with high salinity, low oxygen, and variable water levels in their natural habitats. For example, they have salt glands that excrete excess salt from their leaves, pneumatophores that facilitate gas exchange in waterlogged soils, and viviparous seeds that germinate while still attached to the parent plant. However, mangrove trees are not known to have phytoremediation potential, and their slow growth rate and low seed dispersal make them difficult to propagate and establish.

By combining the genes from mangrove trees and sunflowers, I’ve tried to create a hybrid plant that has the best of both worlds: the stress tolerance of mangroves and the phytoremediation potential of sunflowers.

The project proposes to create a new plant that can improve the quality of polluted or contaminated soils and restore the natural balance of the environment using genetic engineering techniques to transfer genes from mangrove trees into a common sunflower variety.

The candidate genes identified from mangrove trees and sunflowers are involved in stress tolerance, pollutant transport, and gas exchange. These are some of the genes we are going to use:

- For stress tolerance, we are going to use the genes encoding P-type ATPase transporters (HAKT1 and HAKT2) and ATP-binding cassette transporters (HABC1 and HABC2). These genes are involved in the vacuole sequestration of sodium ions and the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. These genes are found in mangrove species and confer high salt tolerance and drought resistance levels.

-

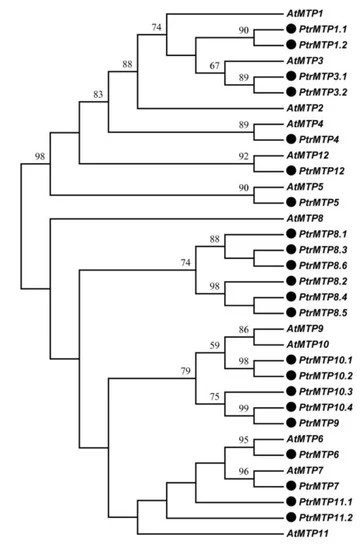

For pollutant transport, we are going to use the genes encoding metal tolerance proteins (MTP1 and MTP2) known as heavy metal associated transporters (HMATs). These genes are involved in metal detoxification and sequestration in plants. These genes are also found in sunflower species, and they have high substrate specificities or affinities for different metals, such as cadmium, zinc, copper, and lead.

-

Relevant HMATs

- HM-associated isoprenylated plant protein (HIPP) family,

- HM-associated protein (HMP) family, ferric chelate reductase (FRO) family,

- an expansion gene (EXPA) family,

- L-Cys desulfhydrase (LCD) family,

- metallothionein (MT) family,

- nicotianamine synthase (NAS) family,

- ubiquitin (Ub)-extension protein (UBQ) family

-

-

For gas exchange, we are going to use the genes encoding photosynthetic and respiratory enzymes, such as Rubisco (RBCS and RBCA), plastocyanin (PCY1 and PCY2), cytochrome c oxidase (COX1 and COX2), and laccase (LAC1 and LAC2). These genes are involved in carbon fixation, electron transport, oxygen consumption, and lignification. These genes are also found in mangrove species, and they enhance the gas exchange efficiency and the carbon sequestration capacity of the plant.

To make these changes, we will use CRISPR-Cas9, a gene editing innovation that uses site-directed nucleases to target and modify DNA with great accuracy. We can design different guide RNAs (gRNAs) that recognise and bind to specific DNA sequences in the sunflower genome and use a Cas9 protein that cuts the DNA at the target site and allows us to introduce mutations, deletions, or insertions of DNA fragments. To transfer these genes into the sunflower cells, we can use plasmid vectors and Agrobacterium tumefaciens to transfer the gRNAs and the Cas9 protein directly into the sunflower cells.

To ensure the success of the new plant, we will comprehensively evaluate the performance and impact of the hybrid under diverse environmental conditions. We’ll assess its growth and survival in various soil types, including sandy, clayey, loamy, and peaty soils, comparing it against non-modified sunflower plants. Additionally, we’ll measure pollutant uptake, examining its ability to absorb metals, organic compounds, radioactive substances, and oil. Moreover, we’ll test its resilience under different salinity levels, ranging from 0 to 500 mM NaCl, evaluating growth, survival, and pollutant uptake efficiency in these varying saline conditions. This multifaceted analysis aims to understand the hybrid’s adaptability and effectiveness in remediating different types of soil pollution.

I believe the proposal is creative and feasible. I hope this hybrid plant will grow in saltwater-contaminated soils and remove harmful substances from the environment while also providing other benefits such as biomass production, seed yield, and ecosystem restoration.

However, it’s important to acknowledge that the proposal has some limitations and challenges. We need to consider the ethical, social, and ecological implications of creating and releasing a genetically modified organism into the environment and the need to ensure the safety and stability of the hybrid plant and prevent any unwanted effects or interactions with other organisms.

Overall, I think this has been a really interesting introduction into the world of designing with biology, a great way to reframe the way we look at how we can create in the world, do all our solutions to the problems we find in the world have to be made by a machine in a factory? Perhaps not. Maybe we can start to see biology as our next big design partner and grow and modify the nature that surrounds us to solve problems that we otherwise couldn’t have solved. 😃

Bibliography¶

Dimitrijevic, A. and Horn, R. (2018). Sunflower Hybrid Breeding: From Markers to Genomic Selection. Frontiers in Plant Science, [online] 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.02238.

Gao, Y., Yang, F., Liu, J., Xie, W., Zhang, L., Chen, Z., Peng, Z., Ou, Y. and Yao, Y. (2020).Genome-Wide Identification of Metal Tolerance Protein Genes in Populus trichocarpa and Their Roles in Response to Various Heavy Metal Stresses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 21(5), p.1680. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21051680.

Hall, J.L. (2003). Transition metal transporters in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 54(393), pp.2601–2613. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erg303. Jan, S. and Parray, J.A. (2016). Phytoremediation: A Green Technology. Approaches to Heavy Metal Tolerance in Plants, [online] pp.69–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1693-6_5.

Ma, D., Ding, Q., Guo, Z., Xu, C., Liang, P., Zhao, Z., Song, S. and Zheng, H.-L. (2022). The genome of a mangrove plant, Avicennia marina, provides insights into adaptation to coastal intertidal habitats. Planta, 256(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-022-03916-0.

nature.berkeley.edu. (n.d.). Bloom of the Week - Phytoremediation with Sunflower. [online] Available at: https://nature.berkeley.edu/blackmanlab/Blackman_Lab/Lab_News/Entries/2013/2/18_Bloom_of_the_Week_-_Phytoremediation_with_Sunflower.html.

Paape, T., Heiniger, B., Santo Domingo, M., Clear, M.R., Lucas, M.M. and Pueyo, J.J. (2022). Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Complex Genetic Architecture of Cadmium and Mercury Accumulation and Tolerance Traits in Medicago truncatula. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.806949.

Parida, A.K. and Jha, B. (2010). Salt tolerance mechanisms in mangroves: a review. Trees, [online] 24(2), pp.199–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-010-0417-x. Yang, Z., Yang, F., Liu, J.-L., Wu, H.-T., Yang, H., Shi, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, Y.-F., Luo, Y.-R. and Chen, K.-M. (2022). Heavy metal transporters: Functional mechanisms, regulation, and application in phytoremediation. Science of The Total Environment, 809, p.151099. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151099.

Zhang, C.-J., Pan, J., Liu, Y., Duan, C.-H. and Li, M. (2020). Genomic and transcriptomic insights into methanogenesis potential of novel methanogens from mangrove sediments. Microbiome, 8(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00876-z.

Resources¶

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969721061775

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2017.02238/full

https://microbiomejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40168-020-00876-z

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.806949/full

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-1693-6_5

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00468-010-0417-x

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00425-022-03916-0